Introduction

In the past five years a new breed of peer-to-peer businesses has disrupted established business ecosystems on a global scale. Collectively known as the sharing economy, these firms seek to create economic systems reliant on the peer-to-peer sharing of goods and services via online marketplaces. The disruptive capacity of the sharing economy is best quantified, with research suggesting that the sharing economy has facilitated $15bn in transactions in 2013 alone, with this predicted to rise to $335bn annually by 2025. Several prominent sharing economy platforms have become indispensable for everyday life, with 44% of US citizens familiar with the sharing economy and 72% agreeing that they could see themselves become regular users in 2 years time. The significant growth and forward-looking potential of the sharing economy is underpinned by growing consensus that access is more valuable than ownership; a statement with which 57% of US citizens agree and one that mirrors the principles of this disruptive economic system.

However, despite its considerable contribution to the global economy, the innovations that characterize the sharing economy have also faced significant challenges. These include the incompatibility with established industry regulations, trust issues by virtue of heightened information asymmetry, and resource inefficiency given decentralization of managerial power.

I will explore how heightened information asymmetry inherent to sharing economy platforms gives rise to trust issues and consequently evaluate the premise: To what extent will asymmetric information inspired trust-issues limit the sustainable growth of the sharing economy?

This premise was chosen due to three factors:

- Personal Experience – I have personally encountered trust issues with sharing economy platforms. For example, whilst planning my trip to Morocco I entrusted a person I had no previous contact with to provide me with accommodation through the Airbnb platform. If that person had no longer been able to provide me accommodation at short-notice, I would have suffered a possible financial loss while finding a place to sleep in a country whose language I do not speak. Given the potential problems arising from counterparty non-performance in context of the co-dependent nature of this platform, I identify trust as a critical issue within the sharing economy.

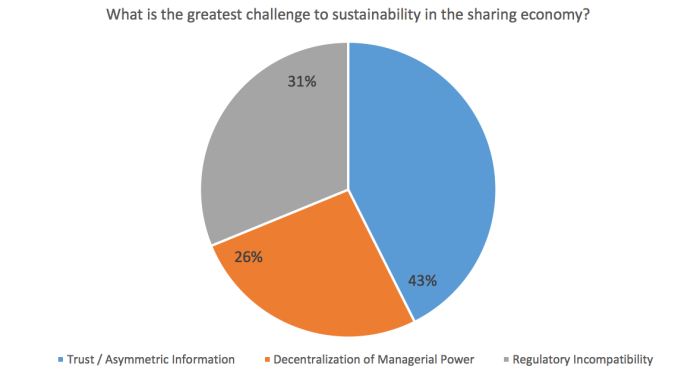

- Public Opinion – According to a PwC report, 57% of experienced consumers in the sharing economy have some concerns about the industry. To accurately serve the interests of my readers, I recently sent out a poll asking which challenges you considered most critical to the sharing economy. The results (Figure 1), indicated that ‘Trust’ was the biggest perceived concern.

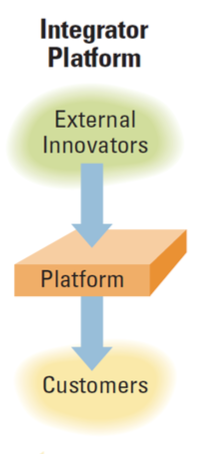

- Theoretical Relevance – The sharing economy employs a commons-based peer production model, reliant on the concept of decentralization. This approach emphasizes a participant driven working ideology, encouraging individuals to self-assign tasks and peer-review the contributions of others; the organization, functioning via an integrator platform, itself acts as an intermediary (Figure 2). Although these characteristics promote information gain and greater variability of human resources, their decentralized nature means that monitoring/responsibility takes place at the individual-level. As such, transactions take place on a citizen-to-citizen basis, lacking the security of traditional business-to-consumer transactions, which exacerbates the issue of trust.

I argue that asymmetric information inspired trust-issues will not inhibit the long-term growth of the sharing economy, given the implementation of effective strategies to attain information parity.

Conceptualizing Trust

Recently, trust’s conceptualization has attracted particular attention from economists, given its key role in transaction cost economics (Williamson 1993) and game theory (Dasgupta 1988). Albeit producing a wide range of material on the subject, the conceptualization of trust has resulted, as Shapiro maintains (1987:625) in ‘a confusing potpourri of definitions applied to a host of units and levels of analysis’.

Acknowledging the incongruence of existing definitions, I however saw a common theme, namely that trust signifies the prevailing degree of confidence, or better said the degree of uncertainty (Gambetta, 1990; Sako and Helper, 1998). In the absence of uncertainty, trust is insignificant, as the outcome is fixed regardless of whether a trusting act is involved. Although uncertainty plays a role, I believe that it does not wholly explain the concept of trust.

I find it fitting to extend our previous definition using that of Bacharach and Gambetta (2001). This definition finds that for a trusting act to occur, two conditions must be fulfilled:

- Exposure from the trustor – the trustor must expose themselves to the trustee in a manner that could make the trustor worse off

- Temptation for the trustee – the trustee must be able to gain from the non-performance of the task, implying that they have the opportunity to profit from violating the relationship

As such, I define trust as a condition that occurs when an individual engages in a transaction exposed to uncertainty, where the trustee exposes themselves to the potential temptation-inspired non-performance by the trustor.

Trust in the Context of the Sharing Economy

In an economic sense, markets operate in equilibrium when perfect information is available to all participants. Often, however, sellers have access to more information on goods/services, given their relative proximity in the value-chain. This phenomenon is known as information asymmetry and can result in adverse selection – a condition in which sellers of high quality goods are unable to justify price premiums, leading to a market saturated with low quality products and stifling demand.

The risk of adverse selection is heightened in the sharing economy, given that platforms are characterized by features unconducive to attaining perfect information. Examples include:

- Limited/non-existent physical interaction – Globalisation has liberated trade from geographic limitations, leading to the formation of highly dispersed and distant trade relationships (Fukuyama 1998). As such, in the absence of physical interactions characteristic of these relationships, the lack of sensory cues inhibits customers from undertaking “the usual process of validation and authentication which traditionally informs our perceptions of trust” (Kwan & Ramachandran 2009)

- Lack of credibility resulting from peer-to-peer transaction relationships – Restating the theoretical relevance of trust outlined in the introduction, the decentralized nature of the sharing economy eliminates the traditional transaction-based credibility of business-to-consumer transactions.

- Reliance on the internet as a principle medium – Given the anonymity of the internet, buyers/sellers can remain unidentified; undermining trust given that individual’s are more likely to engage in opportunistic behaviour when their identity remains hidden. Further, the inability for a customer to physically interact with – and pay for – a product prior to the actual fulfilment of the transaction, represents significant information asymmetry necessitating increased trust.

By virtue of its characteristics, we establish that asymmetric information is inherent to the sharing economy. Considering the work of Pavlou and Gefen (2004), as well as the rational premise that individuals are less likely to trust an individual who retains an informative advantage, in the face of economic benefit, we infer asymmetric information and ‘lacking trust’ to be synonymous in this context.

Mitigating Asymmetric Information: A Theoretical Analysis

Considering the theoretical implications of information asymmetry, we would expect the sharing economy to mirror a ‘Market for Lemons’ – characterized by an oversupply of low quality product offerings. Although, the sharing economy has brought with it a reduction in costs (a PwC study found that 86% of US citizens agree it makes life more affordable), this has not led to a reduction in quality. The fall in prices is rather explained by the fact that sharing is less expensive than individually owning, a finding confirmed by 81% of US citizens. The sharing economy makes use of idle capacity, maximizing the yield an economy retains on products without increasing the total number of products.

The reason why the sharing economy has not befallen the fate of adverse selection is because the industry has made significant efforts to combat this. We will analyse and evaluate two conceptual variations:

- Re-purposing traditional strategies –

- Providing high-quality visual portrayal of the product through a medium (Video/Image) that accurately characterizes the product/offering. According to Wu (2014), the opportunity for a buyer to receive a visual of the product will decrease the information asymmetry inherent to a transaction. As a result, an individual will be able to more comprehensively judge the competitiveness of a product offering, shown to increase consumption. Albeit improving information symmetry, it must be noted that buyers must still trust the integrity of the seller to relate product quality genuinely. (Gefen et al. 2008)

- The integration of an online chat/call function can increase trust, allowing individuals to receive information to which they had no prior access and thereby decreasing information asymmetry and motivating consumption. Further, considering the human aversion to algorithms, this function promotes human interaction, making a transaction more personable while increasing credibility.

- From a payments perspective, most peer-to-peer services integrate security mechanisms to prevent credit-card fraud. Alongside their intended purpose, these mechanisms promote trust by affiliating a platform with recognizable companies, theoretically validated by Mudzakkir (2015) who finds a positive relationship between brand awareness and trust.

- Developing technology/internet-based strategies – Firms operating in the sharing economy have adopted two core strategies that leverage the internet to mitigate information asymmetry.

- Firstly, sharing economy firms intervene directly to take-up transaction risks themselves. This is accomplished through limitations on users accessing the platform, in the form of background checks, credit rating approvals, and criminal records checks. Limiting a platforms user-base, sends a signal of quality to the marketplace given exclusivity of the service. Lyft provides a prime example of this strategy, requiring both a DMV and criminal records check for all registered drivers. This eliminates a significant trust-based competitive advantage of official taxi services, given high user sensitivity to driver quality/safety.

- Secondly, almost every sharing economy platform includes a reputation rating system. A unique example is provided by the Airbnb rating system, which combines written reviews and numerical ratings, aggregating this information to a public profile. This gives both hosts and guests a preconceived idea of the experience to then asses the desirability of the transaction; in a similar way to word-of-mouth and brand credibility at a brick-and-mortar firm e.g. Hilton Hotels. Researchers find that individuals will pay extra for goods given the seller has a high rating, while positive feedback will increase the likelihood of a sale (Eaton 2005). However, it must be noted that rating systems were also found to be subject to bias, given that most users only leave positive feedback and leave more feedback as their experience departs from the norm (Resnick & Zeckhauser 2008), (Dellarocas 2015).

Reviewing the above strategies, we assign additional weight to rating systems given both their practical abundance and the relative importance of peer-to-peer recommendations in the sharing economy. Further, 64% of US adults stated that they felt peer regulation is more important than government regulation in the sharing economy.

We infer that, albeit minor drawbacks, the effectiveness of the theoretical strategies employed to promote trust in the sharing economy is largely supported by academic literature.

Trust vs Growth: A Practical Analysis

I have devised a two-part analysis, analyzing both the general growth of the sector and the impact of trust on a comparable business model: eCommerce.

Firstly, analyzing the growth of the sharing economy in Europe we find that historically the sector has shown significant growth in two key metrics: value of overall transactions and total revenues (Figure 3). Further, we identify that in the defined period, both metrics have grown at an increasing rate suggesting further upward potential. Although it is impossible to quantify the net-cost of asymmetric information on the growth of the sharing economy given the information provided, it is possible to ascertain that its net-cost was not significant enough to stifle growth nor an increasing growth rate.

Secondly, we hold the relationship between trust and growth in the sharing economy to mirror that historically exhibited in the eCommerce sector. We use the eCommerce sector as a proxy as it exhibits many of the same trust-related vulnerabilities such as limited physical interaction and reliance on the internet. A publication by the OECD, identifies a positive relationship between trust and eCommerce growth, finding that eCommerce markets were largest in markets characterized by high consumer protection and competition. This provides practical validation for our assumption that asymmetric information is a net-cost to growth. More significantly, the study finds that consumer trust increased over time in the eCommerce industry, a result likely explained given the mere-growth effect. The mere-growth effect is a psychological phenomenon, which dictates that people develop a preference for things because they are familiar with them. Applying this to the Sharing Economy, we infer that the net-cost attributable to lacking trust will decrease year-on-year.

Case Study: Uber

When considering Uber’s strategy to eliminate asymmetric information, we find that the firm places significant emphasis on its unique two-way rating system. This system allows both drivers and customers to rate each others performance/behaviour on a 5-star scale, aggregating these results to a public profile. In Uber’s words “this rating system does three critical things: it (1) incentivizes high quality service, (2) establishes accountability, and (3) promotes courteous conduct and helps to mitigate the discrimination that is all too common in traditional for-hire transportation.” With relevance to the subject of this post, it is suggestible that the rating system has two core functions. Firstly, as summarized by the three points in Uber’s statement, the rating system refines expectations of service quality given that it ‘establishes accountability’, thereby ‘promoting courteous conduct’. Secondly, the public rating gives both individuals a peer-based indication of service quality – giving the individual a further piece of information to inform their purchasing decision.

Uber has further integrated features to eliminate information asymmetry. The firm has introduced a complaint processing system, which prompts either party to send written feedback to the support team, allowing them to address customer concerns. As previously mentioned, this allows Uber to restrict access to the application for certain individuals, signaling credibility. However, given the intermediary nature of the platform it’s ability to restrict user-access is often constricted by a lack of evidence or conflicting reviews, inhibiting the value of this proposition. Additionally, the platform provides a secure payments system which leverages the credibility of key global players including ApplePay and PayPal, thereby superficially increasing user trust.

To evaluate the success of these strategies, we will consider both user trust statistics and overall growth statistics. Firstly, according to a study by the peer-to-peer lender Rate Setter, over half of Australians trust sharing economy services such as Uber more than their traditional alternatives. Further, I included a question in my email survey that asked respondents to state whether their trust in selected sharing economy platforms had increased over the past 3 years. The results (Figure 4), clearly demonstrate that user-trust in Uber has increased significantly over this period. These two results clearly demonstrate the success of Uber’s strategies to promote user-trust, while the latter also validates the mere-growth effect.

Secondly, looking at the firms growth we consider both Revenue (Figure 5) and Number of Rides (Figure 6). Looking at these graphs, we identify exponential growth in both metrics – a result that suggestively indicates our prior conclusion that net benefits underlying growth > net cost of lacking trust.

Conclusion

To conclude, we must summarise both our theoretical and practical results. Considering our theoretical analysis, the effectiveness of the theoretical strategies employed to promote trust in the sharing economy is largely supported by academic literature. With relevance to our practical analysis, we establish that the net cost of lacking trust < net benefits underlying growth, while we assume that the net cost will decrease given the mere-growth effect. As such, we conclude that lacking trust will not inhibit sustainable growth unless the decline in net benefits > than the decline in net cost. As the sharing economy as a whole has been growing at an increasing rate, while we assume the benefits of economies of scale to be particularly pronounced given the ‘Critical Mass’ component of the sharing economy – our results allow us to suggestively infer that the decline in net benefits < the decline in net cost and consequently that lacking trust will not inhibit sustainable growth in the sharing economy.

Bibliography

Badcock, C. and Gambetta, D. (1990). Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. The British Journal of Sociology, 41(1), p.128.

Cook, K. (2003). Trust in society. 1st ed. New York, N.Y.: Russell Sage foundation.

Dasgupta, G. (1988). The Theatricks of Politics. Performing Arts Journal, 11(2), p.77.

Dellarocas, C. (2015). Designing Reputation Systems for the Social Web. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Finley, K. (2013). Trust in the Sharing Economy: An Exploratory Study. Centre for Cultural Policy Studies, University of Warwick, 2, pp.4-22.

Gefen, D. and Pavlou, P. (2004). The Moderating Role of Conflict on Feedback Mechanisms, Trust, and Risk in Electronic Marketplaces. MIS Quarterly, 1.

Gefen, D., Benbasat, I. and Pavlou, P. (2008). A Research Agenda for Trust in Online Environments. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(4), pp.275-286.

Möhlmann, M. (2017). Why people trust sharing economy strangers more than their colleagues. The Conversation. [online] Available at: https://theconversation.com/why-people-trust-sharing-economy-strangers-more-than-their-colleagues-70669 [Accessed 20 Feb. 2017].

Mudzakkir, M. and Nurfarida, I. (2015). The Influence of Brand Awareness on Brand Trust Through Brand Image. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1(4), pp.30-32.

PwC (2015). The Sharing Economy. Consumer Intelligence Series.

Ramachandran, V. and Altschuler, E. (2009). The use of visual feedback, in particular mirror visual feedback, in restoring brain function. Brain, 132(7), pp.1693-1710.

Ramirez, E., Ohlhausen, M. and P. McSweeny, T. (2016). The “Sharing” Economy Issues Facing Platforms, Participants & Regulators. 1st ed. Federal Trade Commission.

Resnick, P., Zeckhauser, R., Swanson, J. and Lockwood, K. (2006). The value of reputation on eBay: A controlled experiment. Experimental Economics, 9(2), pp.79-101.

Sako, M. and Helper, S. (1998). Determinants of trust in supplier relations: Evidence from the automotive industry in Japan and the United States. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 34(3), pp.387-417.

Weitzl, W. (2017). Measuring Electronic Word-of-Mouth Effectiveness. 1st ed. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Williamson, J. (1993). Exchange Rate Management. The Economic Journal, 103(416), p.188.

Wu, J. (2014). Consumer Response to Online Visual Merchandising Cues: A Case Study of Forever. The University of Minnesota.